Share This Page

Runnin Redbirds

The following is an excerpt from Runnin’ Redbirds: The World Champion 1982 St. Louis Cardinals © 2023 Eric Vickrey by permission of McFarland (McFarlandBooks.com).

Early in the offseason, Herzog re-signed Jim Kaat and added a pair of minor league prospects, pitcher John Stuper and catcher Glenn Brummer, to the 40-man roster. Herzog also spent time laying the groundwork for a trade with the Padres involving Rollie Fingers. Because the 34-year-old closer had only one year left on his contract, Herzog insisted that a contract extension be agreed to before a deal would be consummated. One rumored package had the Cards sending five players—including Terry Kennedy and Tommy Herr—to San Diego.

Herzog selected Dave Winfield and Darrell Porter in the November free agent reentry draft. The system, put in place in 1976, limited the number of free agents that teams could negotiate with in order to prevent big-market clubs from hoarding players. The potential addition of Porter, Herzog’s former catcher in Kansas City, could serve as an insurance policy in case Simmons and Kennedy were needed to acquire pitching. Winfield indicated he had no desire to play for a club in the Midwest, rendering his selection moot.

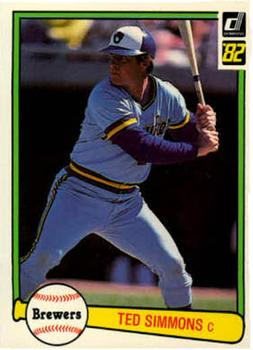

Though Simmons was one of the game’s top hitting catchers, Herzog was not enamored with his defense. “Teddy is a switch-hitter with a lifetime batting average of near .300, but he gave up a lot of passed balls and couldn’t throw worth a damn,” Herzog bluntly wrote in retrospect. The skipper observed that teams tended to steal bases off Simmons rather than attempt to sacrifice runners over, giving them three opportunities to score instead of two. Indeed, Simmons had allowed 116 stolen bases in 1980 and threw out only 31 percent of runners attempting to steal. In contrast, Porter had posted a 46 percent caught stealing percentage in his prior two seasons with the Royals.

Besides Porter’s strong arm, Herzog had appreciated his leadership and ability to handle a pitching staff after coming to the Royals in 1977. The left-hand hitting backstop could also hold his own at the plate, as evidenced by a career .251 batting average and .356 on base percentage at the time. He did not come without baggage, however. Porter had missed the first month of the 1980 season after checking himself into treatment for drug and alcohol addiction. “Knowing Darrell as I did, I was sure that if he said he was okay, he was okay,” recalled Herzog.

Though Simmons was one of the game’s top hitting catchers, Herzog was not enamored with his defense. “Teddy is a switch-hitter with a lifetime batting average of near .300, but he gave up a lot of passed balls and couldn’t throw worth a damn,” Herzog bluntly wrote in retrospect. The skipper observed that teams tended to steal bases off Simmons rather than attempt to sacrifice runners over, giving them three opportunities to score instead of two. Indeed, Simmons had allowed 116 stolen bases in 1980 and threw out only 31 percent of runners attempting to steal. In contrast, Porter had posted a 46 percent caught stealing percentage in his prior two seasons with the Royals.

Besides Porter’s strong arm, Herzog had appreciated his leadership and ability to handle a pitching staff after coming to the Royals in 1977. The left-hand hitting backstop could also hold his own at the plate, as evidenced by a career .251 batting average and .356 on base percentage at the time. He did not come without baggage, however. Porter had missed the first month of the 1980 season after checking himself into treatment for drug and alcohol addiction. “Knowing Darrell as I did, I was sure that if he said he was okay, he was okay,” recalled Herzog.

On the eve of the winter meetings in Dallas, the Cardinals announced the surprise signing of Porter to a five-year, $3.5 million-dollar pact, making him the highest paid catcher in the game. Herzog’s idea was to move Simmons to first base and Hernandez to left field. “I like Ted Simmons,” said Herzog. “I think he’s a winner. Not many guys on this team understand what I am trying to do here, but he is one of them. But…. Darrell Porter is my catcher.” Both Simmons and Hernandez indicated they were willing to go along with the plan.

Weeks of trade talks culminated with a flurry of activity at the start of the meetings on December 8. The first shoe to drop was the Cardinals’ much-speculated acquisition of Fingers from the Padres as part of a massive 11-player deal. Besides Fingers, St. Louis received catcher-first baseman Gene Tenace, left-handed pitcher Bob Shirley, and a player to be named later (catcher Bob Geren) for seven players: Kennedy, pitchers John Urrea, John Littlefield, Kim Seaman, Al Olmsted, infielder Mike Phillips, and catcher Steve Swisher. “At least I’ll be catching the same pitching staff,” quipped Kennedy.

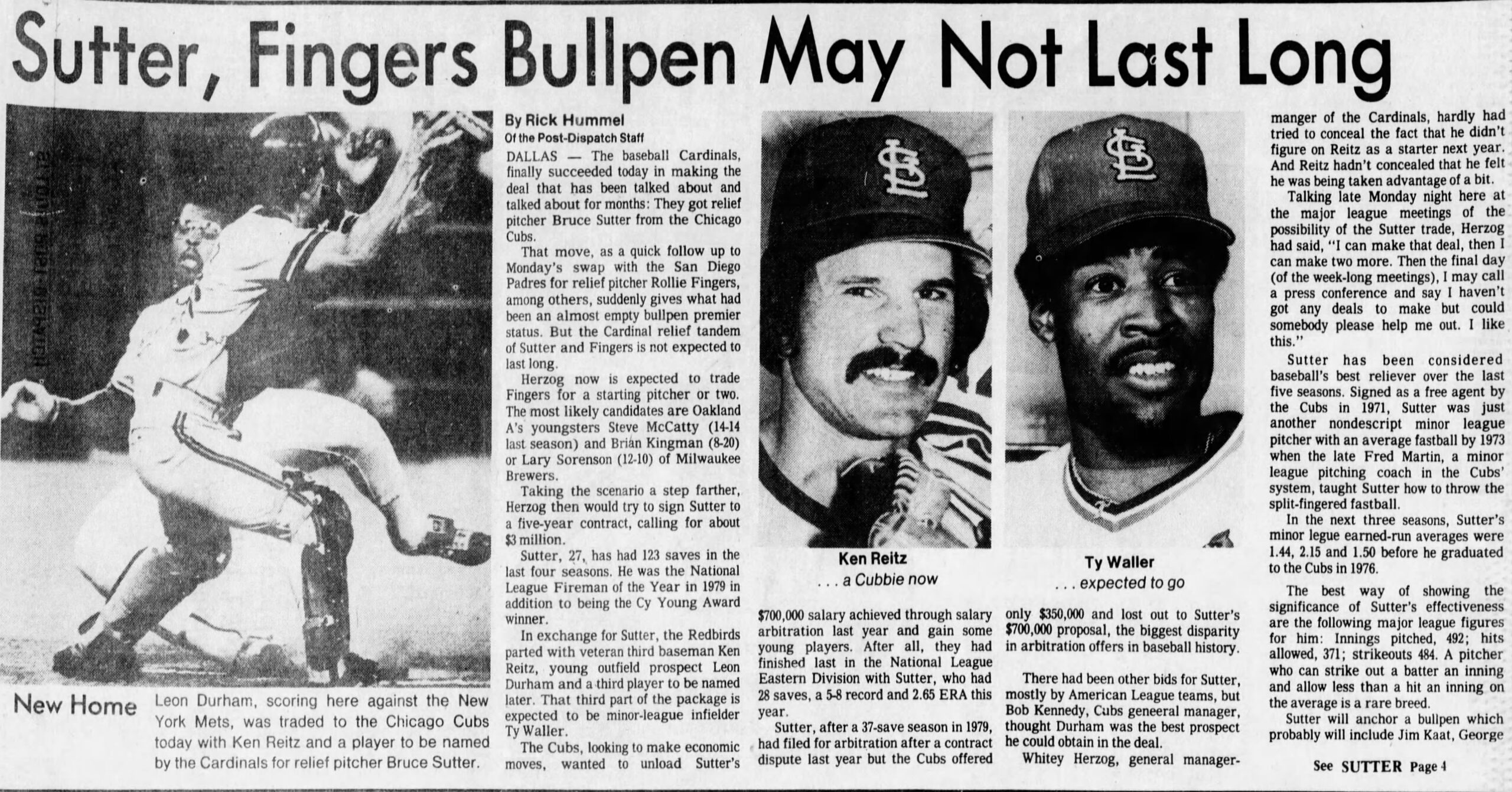

Fingers was a five-time All-Star, three-time world champion, and one of the game’s premiere late-inning relievers. Yet, there was another pitcher Herzog coveted more: Sutter. “I hadn’t given up on getting [Sutter], but with Fingers in the fold, I knew I had some insurance if the deal didn’t come off,” reflected Herzog.

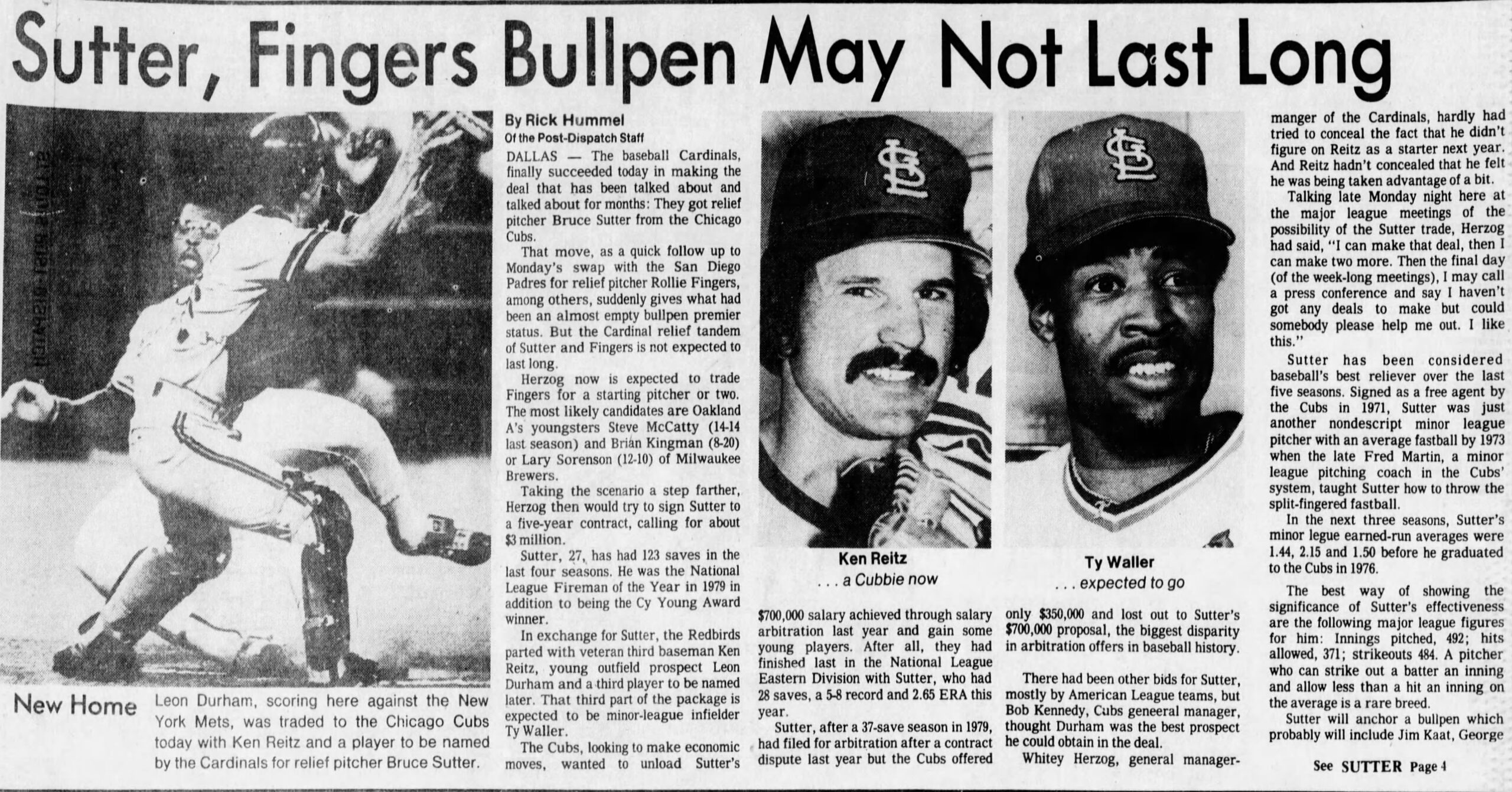

Cubs GM Bob Kennedy, whose son Terry had just been traded by St. Louis, knew of Herzog’s strong desire for Sutter. He wanted three prospects for the all-star reliever: Herr, Leon Durham, and Ty Waller. Herzog did not want to part with the fleet-footed Herr and instead talked Kennedy into taking the comparably slower Ken Reitz, who agreed to waive his no-trade clause for $50,000. Within a matter of hours, Herzog had acquired the game’s two best relief pitchers. With Sutter on board, Fingers could be used as a trade chip.

Just when things were falling into place, Herzog’s plan of moving Simmons to first and Hernandez to the outfield fell apart when Simmons had a change of heart. His agent, Larue Harcourt, asked that his client be traded to a team where he could catch and DH—in other words, an American League team. “I think that [Simmons] was afraid that Keith was so good at first—one of the best I had ever seen—that if he made a mis- take people would compare him to Keith,” said Herzog, looking back.48 Harcourt also made it clear that Simmons, who had 10 years of big-league service and the right to veto any deal, would need to be compensated if traded. “I think we can win with Ted Simmons at first base,” said Herzog at the time. “But if he wants to be traded, we’ll trade him.”

Weeks of trade talks culminated with a flurry of activity at the start of the meetings on December 8. The first shoe to drop was the Cardinals’ much-speculated acquisition of Fingers from the Padres as part of a massive 11-player deal. Besides Fingers, St. Louis received catcher-first baseman Gene Tenace, left-handed pitcher Bob Shirley, and a player to be named later (catcher Bob Geren) for seven players: Kennedy, pitchers John Urrea, John Littlefield, Kim Seaman, Al Olmsted, infielder Mike Phillips, and catcher Steve Swisher. “At least I’ll be catching the same pitching staff,” quipped Kennedy.

Fingers was a five-time All-Star, three-time world champion, and one of the game’s premiere late-inning relievers. Yet, there was another pitcher Herzog coveted more: Sutter. “I hadn’t given up on getting [Sutter], but with Fingers in the fold, I knew I had some insurance if the deal didn’t come off,” reflected Herzog.

Cubs GM Bob Kennedy, whose son Terry had just been traded by St. Louis, knew of Herzog’s strong desire for Sutter. He wanted three prospects for the all-star reliever: Herr, Leon Durham, and Ty Waller. Herzog did not want to part with the fleet-footed Herr and instead talked Kennedy into taking the comparably slower Ken Reitz, who agreed to waive his no-trade clause for $50,000. Within a matter of hours, Herzog had acquired the game’s two best relief pitchers. With Sutter on board, Fingers could be used as a trade chip.

Just when things were falling into place, Herzog’s plan of moving Simmons to first and Hernandez to the outfield fell apart when Simmons had a change of heart. His agent, Larue Harcourt, asked that his client be traded to a team where he could catch and DH—in other words, an American League team. “I think that [Simmons] was afraid that Keith was so good at first—one of the best I had ever seen—that if he made a mis- take people would compare him to Keith,” said Herzog, looking back.48 Harcourt also made it clear that Simmons, who had 10 years of big-league service and the right to veto any deal, would need to be compensated if traded. “I think we can win with Ted Simmons at first base,” said Herzog at the time. “But if he wants to be traded, we’ll trade him.”

Weeks of trade talks culminated with a flurry of activity at the start of the meetings on December 8. The first shoe to drop was the Cardinals’ much-speculated acquisition of Fingers from the Padres as part of a massive 11-player deal. Besides Fingers, St. Louis received catcher-first baseman Gene Tenace, left-handed pitcher Bob Shirley, and a player to be named later (catcher Bob Geren) for seven players: Kennedy, pitchers John Urrea, John Littlefield, Kim Seaman, Al Olmsted, infielder Mike Phillips, and catcher Steve Swisher. “At least I’ll be catching the same pitching staff,” quipped Kennedy.

Fingers was a five-time All-Star, three-time world champion, and one of the game’s premiere late-inning relievers. Yet, there was another pitcher Herzog coveted more: Sutter. “I hadn’t given up on getting [Sutter], but with Fingers in the fold, I knew I had some insurance if the deal didn’t come off,” reflected Herzog.

Cubs GM Bob Kennedy, whose son Terry had just been traded by St. Louis, knew of Herzog’s strong desire for Sutter. He wanted three prospects for the all-star reliever: Herr, Leon Durham, and Ty Waller. Herzog did not want to part with the fleet-footed Herr and instead talked Kennedy into taking the comparably slower Ken Reitz, who agreed to waive his no-trade clause for $50,000. Within a matter of hours, Herzog had acquired the game’s two best relief pitchers. With Sutter on board, Fingers could be used as a trade chip.

Just when things were falling into place, Herzog’s plan of moving Simmons to first and Hernandez to the outfield fell apart when Simmons had a change of heart. His agent, Larue Harcourt, asked that his client be traded to a team where he could catch and DH—in other words, an American League team. “I think that [Simmons] was afraid that Keith was so good at first—one of the best I had ever seen—that if he made a mis- take people would compare him to Keith,” said Herzog, looking back.48 Harcourt also made it clear that Simmons, who had 10 years of big-league service and the right to veto any deal, would need to be compensated if traded. “I think we can win with Ted Simmons at first base,” said Herzog at the time. “But if he wants to be traded, we’ll trade him.”

Weeks of trade talks culminated with a flurry of activity at the start of the meetings on December 8. The first shoe to drop was the Cardinals’ much-speculated acquisition of Fingers from the Padres as part of a massive 11-player deal. Besides Fingers, St. Louis received catcher-first baseman Gene Tenace, left-handed pitcher Bob Shirley, and a player to be named later (catcher Bob Geren) for seven players: Kennedy, pitchers John Urrea, John Littlefield, Kim Seaman, Al Olmsted, infielder Mike Phillips, and catcher Steve Swisher. “At least I’ll be catching the same pitching staff,” quipped Kennedy.

Fingers was a five-time All-Star, three-time world champion, and one of the game’s premiere late-inning relievers. Yet, there was another pitcher Herzog coveted more: Sutter. “I hadn’t given up on getting [Sutter], but with Fingers in the fold, I knew I had some insurance if the deal didn’t come off,” reflected Herzog.

Cubs GM Bob Kennedy, whose son Terry had just been traded by St. Louis, knew of Herzog’s strong desire for Sutter. He wanted three prospects for the all-star reliever: Herr, Leon Durham, and Ty Waller. Herzog did not want to part with the fleet-footed Herr and instead talked Kennedy into taking the comparably slower Ken Reitz, who agreed to waive his no-trade clause for $50,000. Within a matter of hours, Herzog had acquired the game’s two best relief pitchers. With Sutter on board, Fingers could be used as a trade chip.

Just when things were falling into place, Herzog’s plan of moving Simmons to first and Hernandez to the outfield fell apart when Simmons had a change of heart. His agent, Larue Harcourt, asked that his client be traded to a team where he could catch and DH—in other words, an American League team. “I think that [Simmons] was afraid that Keith was so good at first—one of the best I had ever seen—that if he made a mis- take people would compare him to Keith,” said Herzog, looking back.48 Harcourt also made it clear that Simmons, who had 10 years of big-league service and the right to veto any deal, would need to be compensated if traded. “I think we can win with Ted Simmons at first base,” said Herzog at the time. “But if he wants to be traded, we’ll trade him.”

Herzog asked around and initially found two AL clubs willing to deal for the all-star catcher: Oakland and Milwaukee. Simmons, however, did not want to play on the West Coast, leaving the Brewers as Herzog’s only option. After exchanging names with Brewers GM Harry Dalton, Herzog agreed to part with Simmons, Fingers, and Vuckovich but insisted that the Brewers’ top prospect—outfielder David Green—be part of the return. When Yankees owner George Steinbrenner heard about the Brewers’ impending coup, he told Herzog, “You can’t make that deal with the Brewers. You’ll trade them into the division championship!” Steinbrenner swooped in and made an effort to land Simmons and Vuckovich by offering a package centered around Ron Guidry and Ron Davis, but Herzog preferred the return from Milwaukee. In the end, the Cardinals sent Simmons, Fingers, and Vuckovich to the Brewers for Green, outfielder Sixto Lezcano, and pitchers Lary Sorensen and Dave LaPoint. Milwaukee also agreed to supplement Simmons’ current three-year contract by an additional $250,000 per year. The Brewers asked the Cardinals to pay part of the sum, but Herzog shot down that possibility. Dalton was reluctant to include Green, considered one of the best prospects in baseball, but Herzog insisted that without him there would be no deal. Not wanting to risk losing out on Simmons to the rival Yankees, Dalton conceded.

It was an earthshaking trade. Though Sorensen was three years younger than Vuckovich, they were both solid starting pitchers with nearly identical career win-loss records. Removing them from the equation, the Cardinals had ostensibly traded two of the best players in baseball at their respective positions—not to mention future Hall of Famers—for an above average corner outfielder (Lezcano) and two prospects (LaPoint and Green). Many in the industry lauded the Brewers’ end of the deal and felt the talent heading to Milwaukee—a third-place team in 1980—made them a top contender in the AL.

When it was all said and done, Herzog had traded 13 players from the Cardinals’ 40-man roster within a matter of days. “I might be back home fishing by June if this doesn’t work out,” he said at the time. “But we had to make changes. This club hasn’t won anything in 13 years.”

Powered by BlueHost

Monetize your website with Monumetric!